-

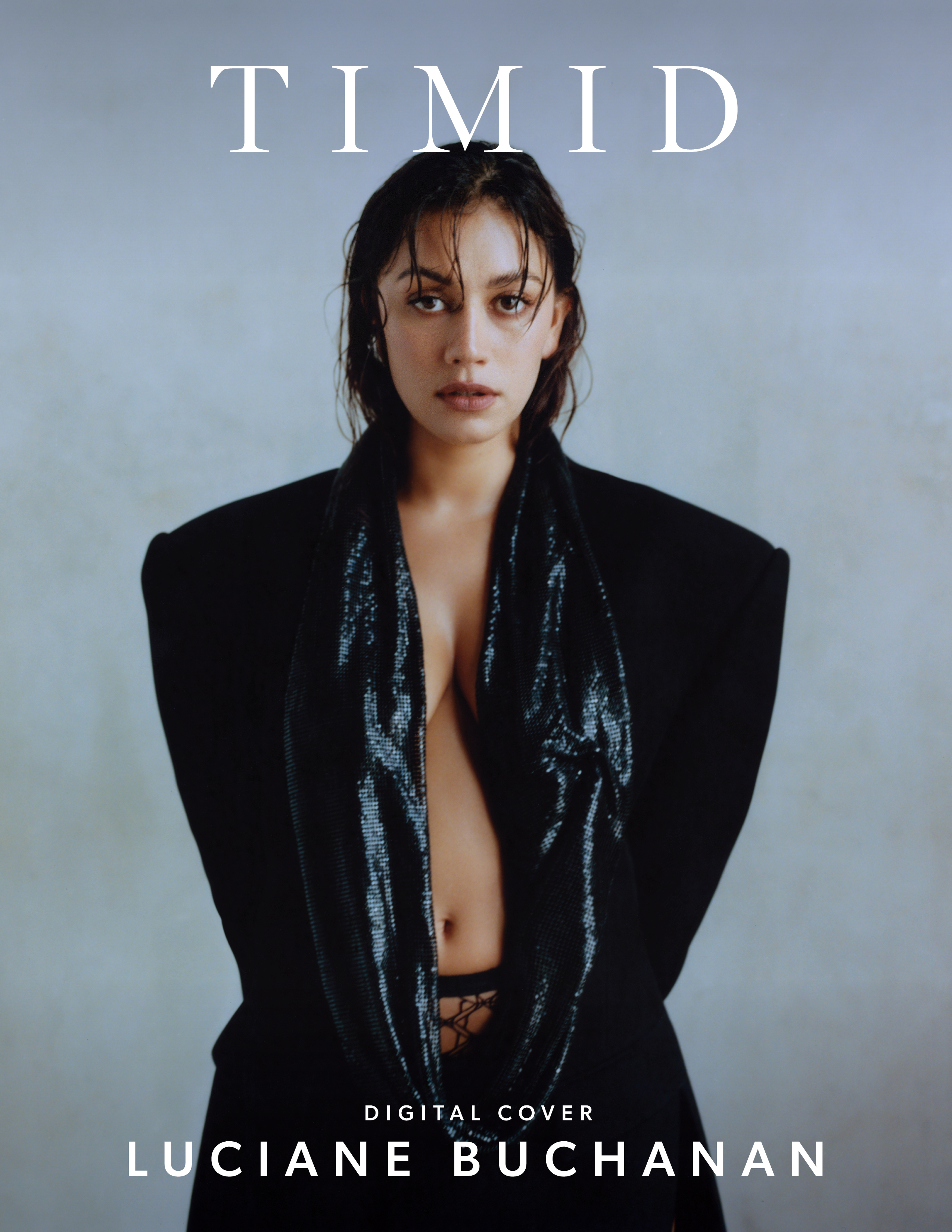

Talent: Luciane Buchanan @lucianebuchanan

Photos: Kiu Ka Yee @kiukayee

Fashion: SK Tang @sktang__

Makeup: Lilly Keys @lilly_keys

Hair: Rena Calhoun @rena.calhoun

Photo Assit: Sean Maydoney @_maydo

Fashion Assist: Juliana Navaa Prado @navaguava

There are some journeys you have to take on your own. Luciane Buchanan didn’t tell anyone on the Chief of War production team she traveled to Hawaii prior to filming the recent Apple TV+ release. The weight of portraying Queen Kaʻahumanu had set in, and she wanted to get to know the influential Hawaiian aliʻi [royalty] on a deeper level. It was a personal quest she felt was necessary, and speaks to the level of care Buchanan has as an actress of Tongan-Scottish descent playing a fellow Polynesian character.

Hailing from Aotearoa, Buchanan started in Oahu at Honolulu’s Bishop Museum, before driving the twisting, hours-long Road to Hana to reach the remote cave where the queen was born. Sitting in the mana [spiritual power] of the cave felt like an “anchor point” to the actress. Her journey ended on Hawaii Island, to view the sacred Naha Stone in Hilo—where, according to legend, the one who flips the massive slab will be the conqueror of the islands—and the heaiu [temple] on the other side of the island in Kona. “It was an opportunity to see the world that she's from, the things that she would have seen in her cave, the ʻāina that she's walked on, just so I had that imagery in my mind before portraying someone of a culture that I'm not from,” Buchanan says.

A historical epic based on true events, Chief of War captures a crucial juncture in Hawaiian history: the bloody, politically turbulent unification of the islands in the 18th century by the prophetic King Kamehameha I under the impending threat of colonization. Kaʻahumanu has a pivotal role in the show as Kamehameha I’s favored wife and trusted advisor as well as a close ally of Jason Momoa’s Kaʻiana, a chief warrior from Maui.

%20copy.jpg)

Against a track record of the over sensationalization and commodification of Hawaiian culture, Chief of War stands out as a rare historically accurate representation, from the shark teeth-laden lei-o-mano weapons to the vibrant ʻahuʻula feather cloaks worn by chiefs, down to the characters speaking in ʻŌlelo Hawaii—the Hawaiian language—until Western contact. For many locals, the careful details and effort into making the show as authentically Hawaiian as possible feels powerful, being that a story from the islands has never been told this way before.

The script spoke to Buchanan just as much. She couldn’t believe her eyes when she had the opportunity to audition for a Polynesian historical drama. She grew up watching film and television and dreamed of one day making it onto the screen herself, but it didn’t seem realistic for someone like her. “I didn't think it was within my reach being from little Aotearoa and being this little Tongan girl, but I guess the landscape of the industry has changed since then,” she says. “More opportunities have opened up for us, not many, but some.” She hopes young people across the Pacific who watch the show can see themselves, and it opens the doors of possibilities for them.

Initially, Buchanan was under the impression that she’d be featured in just a few scenes until American Korean filmmaker Justin Chon, who directed episode one and two, told her she’d be in every episode. Holding her two hands up into a triangle, she mimics how Chon informed Buchanan that Kaʻahumanu was a main character with Kamehameha and Kaʻiana. That’s when she realized Kaʻahumanu was a big deal. “I think, in retrospect, it's kind of good that I had no idea what I was getting into because if I had known who she was and the weight of this kuleana, this duty to portray her, I think I would have maybe not auditioned,” she says, smiling.

Kaʻahumanu’s quiet strength is a stark contrast against the violence and aggression from the male characters. “I know in history, Kaʻahumanu is the one who finishes the job, so how do I find ways to make sure that her influences weave throughout the story?” says Buchanan. “As we know, there's so much war going on today, it's the woman and the children who suffer the most on decisions made by men.” Buchanan advocated for Kaʻahumanu to come across as the complex, nuanced woman she truly was. In the show, Kaʻahumanu wants her Hawaiians to speak English, not out of submission, but to navigate the changing influences and in light of the future of her island home. She fights back against being married, but not because she’s a free spirit. Soon she fearlessly embraces the position as Kamehameha I’s wife with the best interest of her people in mind. “I just want the world to know her name,” she says. “I want people to fall in love with her.”

%20copy.jpg)

To prepare for the role, Buchanan immersed herself in Hawaiian culture, going through what she calls “boot camps” of rigorous studying and practicing cultural aspects led by kumu [teachers]. She sat down with historians and also learned lua, the ancient Hawaiian fighting style. The biggest challenge was not only learning an entirely new language but infusing it into her acting, from the pronunciation to the cadence. “It’s a long process,a very long process, but one that's totally worth it, because this is the first time keiki [children] and Hawaii get to hear on screen,” she says, referring to the fact that the Hawaiian language was banned from being taught in schools in 1896 up until just 50 years ago in 1986.

To work with Momoa—who co-wrote the show and is of Native Hawaiian descent—and to see firsthand how he brought the underrepresented voices of his culture to a global audience has been a major inspiration to her. “I just want people to give them the same reverence or respect that we do with other kings and queens, and other people's history,” she says. “I think this is just the beginning for people unlocking that knowledge.”

Buchanan would like to do the same for her own mother tongue someday, or be behind the camera as an executive producer or director shaping the stories being told. After playing Kaʻahumanu—who will forever live on her “Mount Rushmore of special characters”—she feels like she can take on anything. “Learning a different language and having to act in a different language has given me confidence to be like, okay, maybe I could learn the piano for a role. Maybe I could ride a horse. You know, so I never want to be limited in what I move in. I don’t want to be boxed into a stereotype.” This is only the beginning for Buchanan.